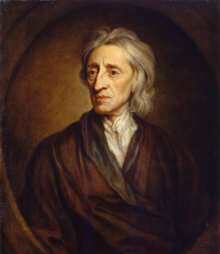

In his essay entitled “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” John Locke, the seventeenth century English “enlightenment” thinker who had vast influence on other thinkers like Voltaire and Rousseau and of course on the American Revolutionaries like Samuel Adams, James Otis and Thomas Paine, said the following,

“For when we reflect on general ideas accurately and with care we’ll find that they are artifacts, contrivances of the mind, which have a lot of difficulty in them and don’t offer themselves as easily as we tend to think. For example, it requires some effort and skill to form the general idea of a triangle (though this isn’t one of the most abstract, comprehensive, and difficult), for it must be neither oblique nor rectangle, neither equilateral, equicrural, nor scalenon; but all and none of these at once. In effect, it is something imperfect, that cannot exist; an idea in which some parts of several different and inconsistent ideas are put together. The mind certainly needs such ideas, and hurries to get them as fast as it can, to make communication easier and to enlarge knowledge. But there is reason to suspect that abstract ideas are signs of our imperfection; and at least I have said enough to show that the most abstract and general ideas are not those that the mind is first and most easily acquainted with, nor what its earliest knowledge is about.” (Book IV, ch. 7, section 9)

In other words…he is saying that there is no such thing as abstractions. There are no universals. There is no such thing as a general idea.

Or rather…these things exist, but only as “contrivances” of the mind!

And why?

Well, as his own example concerning “the general idea of a triangle” illustrates, there is a slight problem. What exactly?

Let’s do a little Socratic dialogue to help make this clearer. We will pretend that Locke is teaching this idea to Langley.

Locke: Ok Langley, so you think that there is such thing as ‘the universal?’

Langley: Yes, I do.

Locke: Would you be so kind as to give me an example?

Langley: Yes, nothing would give me more pleasure Mr. Locke. I have always loved Euclid and so I can think of no universal idea more clearly than that of the triangle. The word triangle is of course a word that signifies the universal concept of a three sided plane figure.

Locke: Ahhhhh, I see. And so you evidently have an idea in your head about a triangle. It is not a specific triangle- but rather a triangle that has properties that every triangle shares? Is this why you call it a universal idea?

Langley: Well yes… quite so.

Locke: Yes, but perhaps you have not really considered this very carefully, my good friend.

Langley: Actually I have been thinking about triangles for as long as I can remember. I don’t see any problem whatsoever in claiming the existence of this universal idea.

Locke: Well let me ask you some questions about your supposedly universal triangle.

Langley: sure

Locke: Does every triangle have three sides?

Langley: Yes

Locke: And must every triangle be equilateral, isosceles, or scalene…or can a triangle be more than one of these at the same time?

Langley: uhhhh….err… would you be so kind as to repeat the question? I don’t quite see what you mean.

Locke: Well, must a triangle either have all its sides unequal, or two sides equal or all three sides equal? Or is it able to be all of these at the same time?

Langley: Well…no…any specific triangle must be one of the three.

Locke: In other words a triangle can’t be, for example, both scalene and equilateral at the same time?

Langley: Quite so…No it cannot.

Locke: Nor can any triangle have only two sides equal and at the same time have all three sides equal

Langley: quite true, quite true

Locke: So when you say that you have a universal idea of triangle… May I ask you which is it? Is your universal idea of a triangle equilateral, isosceles, or scalene?

Langley: Well….I don’t want to say…I mean, I guess it isn’t any one of those.

Locke: But you admitted before that every triangle must be one of the three, did you not?

Langley: Yes I did.

Locke: So which is it?

Langley: Well….I really cannot answer the question. Maybe we could change the subject. Did you hear about the IRS scandal?

Locke: Listen Langley… we need to stick to the question. We need to focus. We need to have intellectual perseverance. We need to follow the logic of the question to its inevitable conclusions!

Langley: Ok but what about the whole Benghazi affair?

Locke: Focus…think…one will never obtain wisdom if one lets his mind dwell on transient political affairs.

Langley: Ok, Ok…so what were you asking?

Locke: You were asserting that you have a universal idea of a triangle. You also admitted that every triangle must be either equilateral, isosceles or scalene- but it cannot be all three of these at once. You admitted that every triangle must have its sides disposed in only one of these ways at once. And so I ask you again… Which of the three is your universal idea? Is the universal idea of triangle equilateral , isosceles, or scalene?

Langley: Uhhhhhh… you know I don’t really get what you are saying and besides I just remembered that there is something that I have to do.

Locke: Maybe you were not cut out for philosophy?

Langley: Well maybe so…I actually was wondering if you know anything about plumbing. You see I have this stack pipe that appears to be a little on the leaky side….

As anyone can see from the above dialogue, Langley was simply no match for John Locke. Langley failed to defend the idea of the universal and so down it went in a flaming mess!

And along with the death of the universal, so died philosophy! So died Theology! So died the perfection of the intellect….and what is left?

The practical!

Well, that was depressing.

Yes…isn’t that just awful?!?

I suppose we need to have a follow up …maybe…

“The universal comes swinging back!”

Son of a gun. Oh well, I guess universals don’t exist. Oops, I just made a universal claim.

Hey maybe particular qualities can’t exist in universal concepts because that would be a contradiction. Oops, I just made another universal claim.

I wonder if Locke could just as easily convince you, Mr. Langley, that the American Revolution was justified.

No I would be much firmer about the Revolution!

That’s what I thought. I would be very interested in hearing THAT dialogue.

Back to universals; if one denies universals then it seems that both materialism and relativism follow. Do you think that relativism comes from materialism or vice versa? Or do they both come from the denial of universals simultaneously?

Interesting…do you mind connecting the dots just a bit for us slower folk? Why do you say materialism follows from the denial of universals?

We arrive at universals by abstracting from particulars. In other words we move beyond what is apparent to our sense experience. If I am not allowed to abstract universal ideas from particulars then it becomes nearly impossible for me to grant that there are spiritual things which exist because I arrive at the notion of spiritual things by moving beyond the physical realties which are immediately apparent. If I’m not allowed to abstract, then I am stuck with particulars and fall into materialism.

Thank you.

That was great. Ok- so why don’t you go ahead and talk about relativism now. How would that follow?

You are cleverly forcing me to reveal my hand before you present your own argument.

Regarding morality, if there are no universal principles then the only way one can make a moral decision is to consider the particulars of the situation. The object of the moral act is no longer a factor. The only other aspects which can be considered are the intention and the circumstances. But both of these things differ from one instance of the same action to another.

For example, I might eat food at one time at home with the intention of satisfying my hunger or I might eat food at a candy shop with the intention of delighting in a sensible pleasure. In both cases the action is the same but the intention and the circumstances are different.

So if there are no universals then the morality of the action is determined merely by aspects which are relative to the individual and the particular situation. Thus relativism seems to follow from a denial of the universal.

Joseph,

I think this whole line of inquiry deserves a whole post!

Funny how mistakes in the intellectual life over seemingly insignificant philosophical ideas can lead to the collapse of any coherent morality as you begin to draw out with logical precision!

Thanks!

Mr Langley

No offense to either of you, but it appears that both of you have completely misunderstood what the great John Locke is saying. He is not saying: ” that there is no such thing as abstractions. There are no universals. There is no such thing as a general idea.” Rather, Locke is warning the thinker, the philosopher and any who might happenstance to read his words. Locke says: “For when we reflect on general ideas accurately and with care we’ll find that they are artifacts, contrivances of the mind, which have a lot of difficulty in them and don’t offer themselves as easily as we tend to think. ” There is no denial of abstractions, universals or general ideas, instead he warns us to reflect upon that which we think we take for granted as being known and understood. It is understandable why a person might jump to the conclusion that Locke denies what you say he does. One sentence inn particular lends to this jump; that being: “In effect, it is something imperfect, that cannot exist; an idea in which some parts of several different and inconsistent ideas are put together.” This sentence says that a true, single general idea of a triangle cannot exist. I found it very telling that neither of you tried to actually disprove what Locke says by attacking his defense of his statement, but rather said that he was wrong and that he had to be because if he was right, then there would be so many truths that exist that in reality would not. Your mascot was morality. Obviously morality needs to exist and No, Locke is not setting up a defense for relativism. If you had tried to disprove his defense through Step by Step thought or the Socratic method you would have found that there is no hole in Locke’s logic and reasoning. A person who does this would admit that there is no true, single general idea of a triangle and that there would, in fact, have to be three general ideas of a triangle that would have to exist at the same time every time a person thought of a triangle for a true general idea to exist. AH AH before you judge me and say that I have done what you accuse Locke of doing read the next line of what Locke says. He says: “The mind certainly needs such ideas, and hurries to get them as fast as it can, to make communication easier and to enlarge knowledge.” This clearly and distinctly is an admission to general ideas and abstractions. Is Locke contradicting himself?! No. What he states next tells what he is saying. “But there is reason to suspect that abstract ideas are signs of our imperfection.” If you put this together with his last sentence a person will see that Locke is saying that not only does man make general ideas and abstractions, but that must make general ideas and abstractions. However these general ideas and abstractions are imperfect. In essence they they are not true general ideas and abstractions. At this point, you may have noticed that that I use the word “true” as a clarifying word quite often. My reason for using this word must be understood in order to understand Locke’s words and my defense of them. In order for a statement to be true it must be 100% factual. If it is not, even if it is 99% factual, then it is not true. For example, when the sentence, “The sun is in the sky.” is used, it is not true. The limits of the sky are the limits of our atmosphere. What is outside our atmosphere is not the sky, but rather is and is called space. The Sun, the planets and other galaxies are in space. If the sun really was in the sky, we would all be dead. However, we would not say that the sentence, “The sun is in the sky.” is a lie. Rather we would say that it is a functional truth. The person reading or listening to this must listen very carefully and thoughtfully for this is possibly the most important of what has been written. General ideas and abstractions are most often not 100% factual and so do not exist as true but rather they exist as “functional truths.” They have part of the facts. When a person thinks of a triangle, they think of something with three sides. However, this not all of what a triangle is by definition and so is not 100% factual. Thus, the everyday person’s general idea of a triangle is not true by the definition of that word. Rather it is a functional truth. It is a concept hurriedly put together by which communication and our ability to know more is made easier. Thus when Locke says that : ” the most abstract and general ideas are not those that the mind is first and most easily acquainted with, nor what its earliest knowledge is about.” he speaks truth. Abstract and general ideas are made only after an understanding of the particular idea is understood. Once understood, a person hurriedly or in an inaccurately concise way condenses the idea into an abstract/general idea that he knows will make sense to him if he has to think of this idea quickly. Thus we can see that the most abstract and general ideas are a secondary phase of understanding.

Why does Locke take his time to explain this? The answer to this is simple. People “store an innumerable amount of ideas in general/abstract ideas and since they are functionally true, they use them as the idea. Locke is reminding us to remember the actual ideas, the true ideas. This is evidenced by the fact that Locke reminds us that we are imperfect, that we need general/ abstract ideas and that he reminds us of what general/abstract ideas really are and what their function is.

Before I leave there is one other problem I must address. That problem is the red herring created by a lack of clarity. The red herring comes in the form of the sentence: “There are no universals.” The writer of this claims that Locke by his words implies this. The first responder ate this red herring up hook line and sinker, by “humorously” opening up with several universal statements. And it was upon this red herring that he based his WHOLE attack. The lack of clarification led to the word universal being used in a way that does not even come close to what Locke was talking about. It would have been permissible, though as untrue as saying that Locke says that there are no abstract or general ideas, to say that Locke denies universal ideas. What the first responder, due to a lack of clarification, turned this into was something completely different. He turned it into Locke saying that no universal claims can be made. As Locke would say, “This is absurd.” To argue and say that there is little or no difference between saying that a person cannot think of a universal idea and a universal claim is absurd. The reason for this is that a universal idea must be grounded in truth, whereas a universal claim is not dependent upon the truth of the statement made. For example, a triangle is a universal idea and as shown above is grounded on truth whether it be true or functionally true. However the claim, “We are all are jellyfish.” though untrue is universal. This having been said, a person must take care not too confuse particular ideas which with little or no thought may seem to be universal. The reason for this is that particular ideas need not be true or even functionally true.

Hi Octavian,

Thanks for your defense of Mr. Locke.

When you say “…that there is no true, single general idea of a triangle and that there would, in fact, have to be three general ideas of a triangle that would have to exist at the same time every time a person thought of a triangle for a true general idea to exist. AH AH before you judge me and say that I have done what you accuse Locke of doing…”

Are you saying that there is no general or universal idea of triangle that is not only “functional” but is also a “true” idea?

Mr. Mosesian,

I respectfully submit that you have misunderstood Locke, the article, and the discussion which followed.

Firstly, it is extremely clear from the text quoted that Locke does not think that universals exist. He says they are contrivances of the mind and that they are imperfect, they cannot exist. For Locke, the universal is something which we talk about as if we know it because that is the most practical thing to do in communication. But really the fact that we speak as if universals actually exist is a sign of our imperfection (according to Locke).

Secondly, the purpose of the article was to show through a dialogue what Locke’s objection to the universal was. You want to accuse the article of failing to disprove Locke’s position. If you want to go ahead and disprove the idea that universals don’t exist then feel free. I personally am not going to waste my time disproving a denial of something which is blatantly self-evident. If there were no universals then we couldn’t even argue about whether they exist because the whole purpose of an argument is to show logically that something is true, which implies necessarily that there are universals.

Thirdly, the discussion which followed the article was not about Locke’s denial of the universal. It was about how materialism and relativism follow from a denial of the universal. The real red herring is your claim that those involved in the discussion failed to address Locke’s defense of his position. The discussion was never about “attacking” Locke’s argument in the first place. It was a consideration of the logical consequences of Locke’s position.

Fourthly, the lack of clarification is on your end rather than mine.

Number one: universal ideas are not necessarily grounded in truth. Someone can have a universal idea in his head and it could certainly be false. In fact, it happens ALL THE TIME.

Number two: a universal claim is an expression of a universal idea. If you think I’m making this up then just look up what the words “idea” and “claim” mean.

Number three: Locke thinks that universal ideas are a sign of our imperfection but that we use them anyway to communicate and to enlarge knowledge. So if I make a universal claim (an expression of my universal idea) that’s a sign of my imperfection according to Locke. Hence the comical “oops!” is a reaction to letting a sign of my imperfection slip. It is ironic that Locke is betraying his own imperfection by claiming that universals do not exist.

Fifthly, if you want to claim that “General ideas and abstractions are most often not 100% factual and so do not exist as true but rather they exist as “functional truths.” They have part of the facts,” then you need a different example because it is manifest from common experience that EVERYONE understands that a triangle is a plane figure contained by three straight lines (even if they do not use such precise language). And guess what? That IS the definition of a triangle.

Finally, Locke says at the end of the quote from the article that he has said enough to show that general ideas are not the first which are presented to the mind. Wow, what an original idea! Oh wait, Aristotle said that all knowledge begins with the senses, which means that it begins with particulars. Of course general ideas are not the first which are presented to the mind! We knew that long before yet Locke talks about it as if his brilliant essay is the first to discover it.

Oh and one last thing, just to satisfy me. You claim that the sun is not truly in the sky. Do you believe that because a man in a white lab coat told you? Or do you have scientific knowledge?

I am very interested to hear your answer to Mark Langley’s question.

Great post and discussion!

I don’t know if this is relevant to ask, but is Locke’s main error in his line of reasoning the fact that he tries to mix details of particular triangles with the universal idea of triangles, or is Locke being more subtle, and suggesting that the universal idea of triangle is dependent upon a phantasm of a triangle, which obviously must be particular?

Hi Daniel,

I think you are right in your first statement- and also in your second statement about Locke suggesting that the universal idea of triangle is dependent on the particular triangle that we have in our imagination.

In either case Locke gives us a magnificent example of someone who does not appreciate Aristotle’s distinction of the word “in” in Book 4 of his Physics. The third sense of “in” is the sense that we say the “species is in the genus.” (And Aristotle explains the way that the species is in the genus later)

Locke appears to be unaware of Aristotle’s teaching concerning the difference between potency and act- and that the species in in the genus not in act– but only in potency.

So in other words – the next time I have a dialogue with Mr. Locke – when he asks “So Langley…is the universal idea of triangle equilateral, scalene or isosceles?”

I am going to say: “Mr. Locke, the universal is all of those in potency but none of them in act!”

And I think that should send him away quite nicely!

The only thing I seem to be able to add to this kerfuffle is something that is already probably quite clear but has not yet been stated: the conclusion to the Socratic dialogue that occurs between Locke and Langley. Had Langley not been unfortunately distracted by the IRS and plumbing, he might have succeeded in changing Locke’s understanding of triangles, thus possibly causing Locke to experience a conversion and become a prominent Catholic philosopher. Who knows?

In the Socratic Dialogue that occurs between Locke and Langley, I simply wish that Langley would have chosen to make the point that the universal definition of a triangle (“a three sided plane figure” as he called it) does not in any way negate the possibility of those sides being equal or not. The argument given by Locke in this specific article breaks down when he asks, “So when you say that you have a universal idea of triangle… May I ask you which is it? Is your universal idea of a triangle equilateral, isosceles, or scalene?” This question does not acknowledge that a triangle is a “three sided plane figure” and that all triangles (equilateral, isosceles, or scalene) conform to this definition of a triangle. In other words:

1. All triangles have three sides.

2. Equilateral, isosceles or scalene triangles have three sides.

3. The length or equality of those sides is irrelevant to their existence as triangles according to the definition of triangle.

4. The “universal triangle” in the head of Langley is one that has three sides (regardless of length). All of Locke’s examples of various triangles have three sides. Therefore Langley is correct in stating that their is a universal concept of triangle that is universally true. Locke would have to agree that all of his examples have three sides and therefore conform to the definition of a triangle.

5. Langley – 1. Locke – 0.

To go back to the original source, Euclid’s 19th definition states: “Rectilinear figures are those which are contained by straight lines, trilateral figures being those contained by three, quadrilateral those contained by four, and multilateral those contained by more than four straight lines.” Note that the trilateral figure is that which is contained by three sides. He then goes on, with his 20th definition, to state: “Of trilateral figures, an equilateral triangle is that which has its three sides equal, an isosceles triangle that which has two of its sides alone equal, and a scalene triangle that which has its three sides unequal.”

To summarize, it seems to be the case that regardless of the equality of the sides of a triangle, a triangle will always have three sides. The universality of a triangle does not lie within the particular lengths of its sides, but rather in the simple truth that it has three sides. Is there a triangle that does not have three sides? No. Therefore, the universal truth is that a triangle, by necessity, must have three sides, regardless of the length or equality of its sides.

Again, I am probably stating something that was already agreed upon, (and looking back I was probably a little to repetitive in that endeavor) but I would have liked to have seen that concluded in the Socratic dialogue. I simply felt bad for Langley. I do hope his plumbing problem worked out.

I see no need to address Mr. Mosesian’s response, as Mr. Gonzalez seems to have dealt with it quite aptly. I do await Mr. Mosesian’s response quite eagerly.

Thank you for sending this my way, Joe, and thank you for taking the punches Mr. Langley. God Bless you all,

– Leo

Ok first of all joe he says that general ideas are contrivances of the mind. And they are. Locke in no way states that universals do not exist. There is a major difference. I already addressed this matter in my last post. General ideas, and in no way alluding to universals, exist as a sign of our imperfection. You are making the exact mistake that Locke is trying to warn about.

Secondly, your second objection does not make logical sense. It is perfectly valid for me to say that this article does not disprove Locke’s position, not because I am saying universals don’t exist. Rather it is because I am saying that the writer of the article is accusing Locke of saying what he does not say and so errs. To make it ridiculously clear of what I am saying I shall provide an example. If person L said people use guns to kill people and person J said “See L says that guns kill people.” And then wrote an article about it. I would say that is not what L is saying.

Your third objection falls far short. Why? Because an intellectual discussion based upon a faulty premise, no matter how beautiful and logical the conclusions drawn from that premise, is still a faulty discussion and so the conclusions are faulty. In other words, in an honest intellectual argument it is imperative to examine and ensure that your premise is not faulty. Your subsequent discussion was based upon a faulty a premise, that being that it was assumed like was saying what in fact he was not.

For your fourth objection, I shall simply ask, did you read and comprehend what I wrote about universal ideas and universal claims. Also a universal idea is not an expression of a universal claim. I did look it up. An idea is “A concept or mental impression.” Whereas a claim as a verb is to “State or assert that something is the case, typically without providing evidence or proof” and as a noun it is “An assertion of the truth of something, typically one that is disputed or in doubt.” Thus as I previously stated very clearly in my last post a universal claim needs not be 100%factual.

Before I address your fifth objection I want to address your last 2 1st. Your second to last is an ad hominem towards Locke. And the ridiculousness of this attack is astonishing. By saying that Locke is not being original because Aristotle thought of it first implies that any idea or topic that a philosopher uses that Aristotle uses should be up for ridicule because it is not original. Is that because Aristotle’s word is final? If not then, Aristotle’s works ought to be set up for ridicule because Socrates and the pre-Socratics addressed topics and ideas that Aristotle exmines.

To your last argument, A: is Halley’s comet in the sky? Do you believe Solar eclipses are not real? And B if you are implying that scientists make these things up, then you should really start to question the validity of the science behind much of the technology you take for granted as they were arrived at in a very similar way. And C Mr Klucinec does not dress in a white lab coat and he taught me physics. In that class we learned a lot about space and how we know where things are in space.

Until you are more academically serious, objection 5 will be the last objection of yours that I answer as I have no desire to waste my time with half thought out or emotionally driven objections.

As for objection 5, Locke and I use the triangle, because it is so readily understandable as is the universal claim we are all jellyfish. And yes every1 knows that a triangle has 3 sides. The fact that you bring this up again shows your lack of understanding of what Locke is trying to say.

To Mr . Langely I say

For your question: “Are you saying that there is no general or universal idea of triangle that is not only “functional” but is also a “true” idea?” I would ask that you take out the word universal. Locke leaves it out because there are so many aspects to the word universal (so many ways it can be understood) that it only becomes a deterrent. I showed briefly in my last post the different ways universal can be thought of and so as Locke foresaw the word general should be used. Now to answer your question, my answer is yes. There is no general idea of triangle that is not only functional but is also a “true” idea. This is so for the same reason why your “potentiality” explanation does not work. You say that your answer is that the general angle of a triangle” is all of those (equilateral, scalene or isosceles) in potency but none of them in act!” However this is the very difficulty that Locke points out: “the general idea of a triangle… must be neither oblique nor rectangle, neither equilateral, equicrural, nor scalenon; but all and none of these at once.” From there he says: “In effect, it is something imperfect, that cannot exist. In fact you end up supporting Locke. Locke is saying that the “true” general idea of a triangle has the potential to be equilateral, scalene or isosceles or as you put it: “it is all of those in potency.” Yet the general idea of a triangle has to be none of these( or as you said, “none of them in act”) because the equilateral is just as “qualified” as the scalene or isosceles, and the scalene as much as the equilateral, or isosceles and the isosceles as much as the equilateral or scalene. In order to have a 100% factual idea of a triangle aka a “true” general idea of a triangle it is necessary to have the 3 types present. It is not enough to say that the definition is that is a3 sided figure. The proof of this is the definition of a square. A square is a 4 sided figure. However, that is not enough of a definition as it doesn’t impart enough necessary information. It is obligatory to add that all the sides are equal. Or with a rectangle, it is obligatory to state that the parallel sides are equal. If this is left out than the person could and would think that a trapezium is a rectangle of sorts. Just as a person cannot leave out the lengths of the sides for a square rectangle or a trapezium, so to the sides are necessary for a “true” general idea. Locke is merely pointing out that are general ideas are not as “true” as we take them for granted to be. As a concluding example, let us examine the word: human. That seems easy enough. It’s a bipedal animal with 2 arms that is different from the other animals because it has rationality. Ok. Is your idea of a human, male or female? What color is your person? Color does matter; because although a black, brown, white, oriental yellow( I don’t actually know what color that falls under) are all acceptable color still matters. If for example you saw a green bipedal animal with 2 arms that is different from the other animals because it has rationality, the… would be considered humanoid. While you wouldn’t run into a humanoid on the street, if you have seen any science fiction movies, like the 2nd most recent star treck movie, you will have the idea of a humanoid in your mind. Thus in order to have a “true” general idea of a human it must be a bipedal animal with 2 arms that is different from the other animals because it has rationality, but also the gender and the color must be taken into consideration. Thus a person would have to have at least 8 different general ideas and none of them at the same time in order to have a “true general idea of a triangle. This doesn’t mean that we don’t have a general idea of a human or a triangle, but as Locke warns us that, due to our imperfection (unless you are God), general ideas are “artifacts, contrivances of the mind” that do not don’t offer themselves as easily as we tend to think because they are not as complete as we take them for granted as being. All this being said, Locke is not trying to criticize, humanity by showing us our flaws, but just as a tutor(teacher) in college tries to make us aware of what we do not notice to notice so that the way to thinking more clearly is open to us Locke is making apparent what we might not notice. Indeed his being so misunderstood evidences his need to do so.

Isn’t saying that “universal ideas are contrivances of the mind” effectively saying that they have no existence? A four-headed beast is a contrivance of the mind, a I suppose one could say that the phantasm of this four-headed beast is “real,” but that comes perilously close to semantics. If our universal ideas have no more existence that my phantasm of the giant blue rabbit in my living room, this is not giving universals much “existence,” wouldn’t you say?

I believe when Mr. Langley speaks of universals,” he is referring to the Aristotelean understanding of this term. You state that “This sentence [of Locke] says that a true, single general idea of a triangle cannot exist.” But this is precisely what Aristotle means by the universal idea of a triangle. If Locke denies this, he is denying the existence of universals, as commonly understood.

Now it may be that Locke is attempting to “save” the idea of the universal by redefining it in what he sees as a more logical way, and this would not be an uncommon way of proceeding for the so-called “Empiricists” (Locke, Berkeley, Hume). Berkeley attempted to do this with cause and effect. To take an extreme example, if I redefine God in such a way that it empties the concept of its essential content (e.g. I deny his omnipotence, or his eternity), I am effectively denying his existence, even as I deny this denial in words.

Now some philosophical concepts may need redefinition; Aristotle certainly did this vis-a-vis the Pre-Socratics and Plato himself. One may certainly debate the meaning of “motion” or “time,” but there must be agreement on the basic phenomenon.

As often happens, arguments, both philosophical and otherwise, revolve around the meaning of terms.

Until you understand that there is a difference between the word general idea and universal idea an know what that difference is then you will not understand what Locke or I am trying to convey.

As far as I can tell, neither “general idea” nor “universal idea,” as Locke uses the terms, corresponds to what Aristotle meant by “universal.” Or, to put it more precisely, Locke (as you interpret him) seems to have placed additional strictures on what a universal is so as to effectively cancel what Aristotle meant by the term. Hence, I don’t think it’s completely inaccurate to say that Locke denied the existence of universals, since, as I argued above, redefining the term in as radical a way as Locke does effectively denies its original meaning.

General ideas and abstractions are most often not 100% factual and so do not exist as true but rather they exist as ‘functional truths.’ They have part of the facts. When a person thinks of a triangle, they think of something with three sides. However, this not all of what a triangle is by definition and so is not 100% factual.

The fact that a “three sided rectilinear figure” cannot exist independently of the mind (there can be no such creature as a three sided figure that is in fact not isoceles, scalene, or equilateral) does not mean that it cannot exist in the mind. Locke is assuming that any concept must have a correspondence to an actually existing thing (be “100% factual”), but this is not at all what Aristotle understood by a universal. Abstraction means precisely that: that we have abstracted (lifted out) the essence of a triangle from how it exists in the world.

One indication that “three sided rectilinear figure” is an adequate idea of a triangle is that it is an infallible test as to whether the figure before us is a triangle or not. True enough, there will in fact be some relationship among the sides (none, two or three equal), but this does not enter into our “test,” which is an indication that it has no part in the universal either.

It may be that certain people make a mistake when it comes to the definition of something, thinking that “four sided rectilinear figure” is an adequate idea of a square. But it does not follow from this that the mistake lies in the failure to have the idea correspond to a thing that can actually exist. It may just be that the definition is too broad for the thing at hand.

One final thing – there seems to be some confusion between “universal idea” and “definition.” A definition is a proposition giving genus and species; a universal idea is the essence of the thing as abstracted by the intellect. The former is a expression of the latter (and this expression may be adequate or inadequate, as the above discussion shows) but the two are not the same thing.